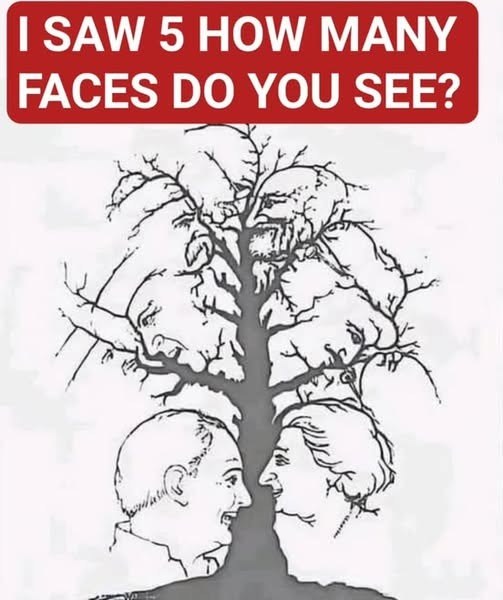

Is It Possible to Find Every Face Hidden by This Optical Illusion?

The “Tree of Faces” illusion continues to fascinate people because it blends history, art, and psychology into one timeless puzzle. At first glance, it looks like a simple drawing of a tree with spreading branches and curling leaves, but as the eyes adjust, faces begin to appear where none seemed to exist. This moment of discovery—when hidden human features suddenly emerge from the patterns—creates a deep sense of wonder. It reminds viewers how perception can shift in an instant and how the human brain constantly seeks familiarity, even in abstract shapes.

The illusion is thought to have first appeared in the late 19th century, possibly in Harper’s Illustrated, when hidden-image puzzles were immensely popular. Such illustrations reflected the growing Victorian interest in both science and imagination. The “Tree of Faces” in particular captured people’s curiosity because it invited not only observation but interpretation. Was it merely an artistic trick, or a coded representation of real figures who shaped history? The inclusion of what seem to be the faces of presidents, world leaders, and influential personalities transformed it from a drawing into a historical riddle.

Psychologically, this image is a classic demonstration of pareidolia—the human tendency to perceive familiar patterns, especially faces, in random designs. The brain is wired to recognize faces more than any other shape, an evolutionary trait linked to social survival. When people look at the “Tree of Faces,” they experience a brief mental puzzle: their perception shifts between seeing an ordinary tree and recognizing a group of hidden people. This back-and-forth perception keeps the brain active and intrigued, which explains why the image still circulates widely online.

Culturally, the illusion also plays on people’s fascination with mystery. In the digital era, where information moves fast and attention spans are short, timeless puzzles like this offer a rare form of slow engagement. Searching for faces in the branches requires focus, patience, and curiosity—the very qualities that modern life often pushes aside. It gives a satisfying reward for effort: the joy of finding something that others may have missed.

Another reason for the illusion’s continued appeal lies in its adaptability. Different audiences see different things. Some claim the faces belong to historical leaders such as Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, or Mikhail Gorbachev. Others believe the features resemble Indian political icons or European monarchs. The ambiguity allows every viewer to project their own imagination and cultural knowledge onto the picture, turning the act of looking into a personal interpretation.

Beyond entertainment, the “Tree of Faces” also serves as a subtle reminder of how intertwined human perception and meaning are. It challenges people to look beyond the obvious, to pay attention to details, and to recognize how easily the mind fills in blanks. In classrooms, it can be used to teach about optical illusions, art composition, or even cognitive psychology. On social media, it thrives because it invites friendly competition—who can spot all the faces the fastest?

In the end, the “Tree of Faces” remains fascinating because it connects generations through curiosity. It’s more than just a hidden-image puzzle; it’s a window into how humans see, think, and imagine. The same drawing that amazed readers in the 1880s now entertains millions online, proving that while technology changes, our sense of wonder does not.